François Ozon's Swimming Pool: The writer as voyeur

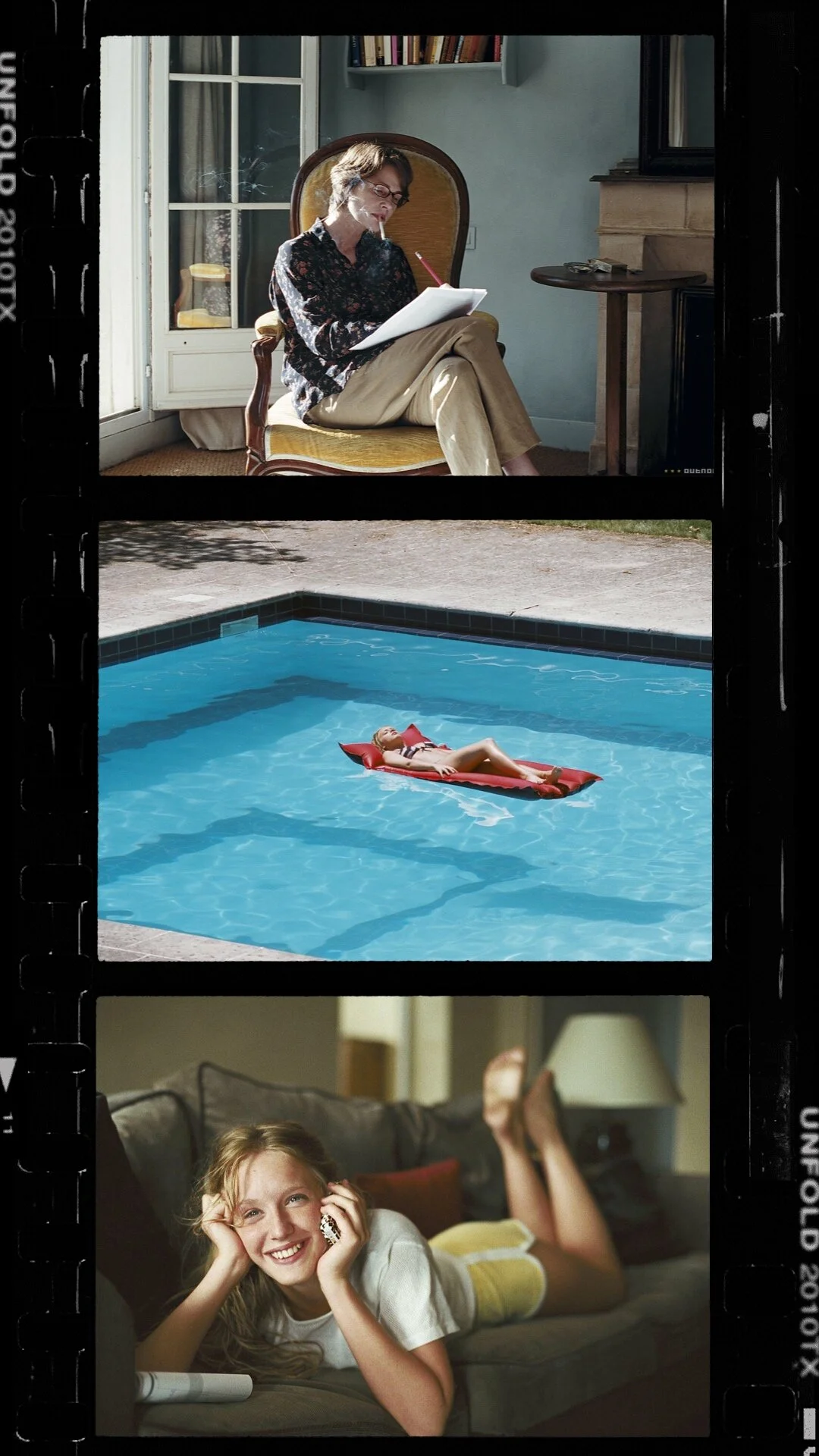

François Ozon's 2003 erotic thriller Swimming Pool follows Sarah Morton (Charlotte Rampling) a successful yet dissatisfied crime novelist as she spends some time away from stuffy England at her publishers home in France.

Spoilers ahead…

From the get-go Morton is uptight and bizarre, her excessive consumption of yoghurt is rather uncanny, her interaction with a fan on the tube and simmering jealousy of a new writer is telling. She’s going to undergo a metamorphosis and become less stoic and boring by the end of the film. But how she gets there is going to be rather interesting.

Morton is also a voyeur, she watches Julie (the daughter of the publisher whose house Sarah is staying at) have sex with a random stranger one night and often finds herself watching her when she swims and also becomes irritated by Julie talking and laughing on the phone. A weird obsession grows. There's also a scene in Sarah’s imagination where the camera tracks the contours of Julie’s body as she sunbathes, it’s almost the male gaze at work but it’s actually Sarah’s gaze, her authorial imagination at work.

I feel like the writer as a voyeur is such an obvious yet intriguing trope in thrillers. I mean writers definitely have to be voyeurs to some extent, people-watching is a socially acceptable form of voyeurism. But a thriller always makes them a little more creepy, and to be honest, Rampling makes this trope work so well that it almost feels fresh again.

“When someone keeps an entire part of their life secret from you, it's fascinating and frightening”

However, this is when things start to get complicated, Julie reads Sarah’s book and invites the local waiter Frank (to who Morton has taken a liking) over to make her jealous, they party. The morning after a panicked Sarah sees the pool covered up with a lump in the middle of the tarpaulin. Is Frank dead? No, it’s just the inflatable lilo. This moment was done well, it was predictable but it still makes your skin crawl for the duration of the scene.

Unsurprisingly, Frank does actually turn up dead, the two women bury him and vow to get on with their lives, Sarah even has to seduce the gardener after he starts to inspect the grave they dug the night before.

But this is all a ruse.

The entire plot of the film is put into question when an emboldened Morton returns to London with her finished novel and announces to her publisher that she has signed with someone else to release the book. Upon leaving the office a young girl enters and is addressed as Julie and greets her father. The Julie in France is not the real Julie in fact she never existed at all!

What a brilliant twist. She’s just an over-imaginative and slightly perverse writer. The metamorphosis I mentioned earlier happens because she gets her inspiration back, she blooms again because she has written something that excites her. I love how Ozon weaved this narrative and for a while, I thought it was going to follow an obvious course but I was really pleasantly surprised.

Ozon himself said ‘Charlotte's character kept mixing fantasy and reality. Although in Swimming Pool, everything related to fantasy is part of the act of creation, so it is more channelled and less likely to end up causing madness. In terms of directing, I've treated everything that is imaginary in Swimming Pool in a realistic way so that you see it all – fantasy and reality alike – on the same plane.”